During the period of Parisan modernism of 1860-1890 there existed a patriarchy within the spaces represented by the artists in terms of their gender creating a weighty restriction to female artists whilst creating the utmost amount of freedom for the male artist. The paintings of practitioners such as Manet, Monet, Renoir, and Degas possess great variety in their representation of modernity ranging from the Ladies and prosperous families of the theatre, park, bedroom, drawing room and house grounds, to the Fallen Women of the brothel, café, folies and backstage at the theatre. What is interesting is that female painters such as Cassatt and Morisot are restricted to only the Ladies and families that the previous painters have access to, not once creating works in which the courtesan or the prostitute become the subject matter.

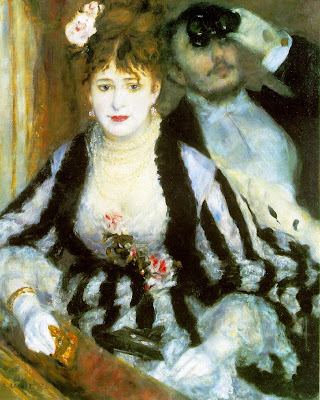

Renoir, The Loge (1874)

We can the difference in the spatial relations of representation that male and female artists envisage within identical social spaces, here we see a greater gender gap appear within the realms of social structure. The Loge (1874) by Renoir and The Loge (1882) by Mary Cassatt resemble the almost identical scene of a box at the opera, however both hold considerable differences in their composition and representation of the scene. For instance, in Renoir’s piece we can observe a well-dressed lady sitting in the loge at the opera; however her attention is not focused on the show at hand, rather towards the male spectator who exists as both Renoir in pre-composition and ourselves as the viewer. Her facial expression suggests she is delighted by her male observer sharing in his excitement, yet does so in a submissive manner as she does not appear to be aware that she is offering herself as a spectacle for both ourselves and for the male figure behind her; this character himself does not actually acknowledge her presence as his eyes wander upwards, possibly towards another woman. The lack of self-awareness, as the ‘young woman lets herself be admired’ [1], allows for the viewer to enjoy her all the more due to her submissive nature and beautiful garments which attract the male bourgeoisie around her; ‘the women in his paintings are never given an active role; their beauties are displayed to the eye, put at the disposal of a male viewer’ [2].

Cassatt, The Loge (1882)

Cassatt’s image on the other hand is composed on a polar-opposite, unlike Renoir’s comfortably seated courtesan the two ladies in the scene sit stiffly erect in their postures, ‘ramrod straight, awkwardly clutching a fan before a face or a bouquet of flowers held a little too tightly on the lap’[3]. Their faces, with unenthused expressions hinting at vast feelings of tedium veer towards the show rather than the viewer/spectator in a desperate attempt to immerse themselves in the world away from that which they are situated in. Signified here is a feeling of unease, constraint and suppressed excitement due to the introduction of a public space that is scary and daunting, as they are paraded ‘exposed and dressed up, on display’ [4]. The girls possess a self-awareness of being placed on display for others in their appealing clothes which we can see from their rigid appearance; the image refuses to comply with the norms of the day and counters the view of femininity expressed within Renoir’s piece. Interestingly, the figures also appear to attribute their own sense of a gaze in which their interests focus towards an independent perspective, geared away from surveying their own actions in order to impress those who stare.

In relation to pictorial space, Cassatt paints her scene within the reach of her own arms length suggesting that she too is nestled close to the figures, possibly knowing them on a personal basis. The piece is also composed at an oblique angle which places the two figures off-centre in the piece, thus disallowing the girls to be framed and ‘made a pretty picture for us as in [Renoir’s] The Loge’[5]. This element is persistent in many female impressionist works, including Cassatt’s

Morisot, The Cradle (1872)

The elements thus brought forth are direct results of the new developments in culture that have been presented; in the 1880s Modernity had offered new class divisions within the bourgeoisie – cafés, the brothel and the opera fashioned new pastimes for the current members of society, but with these new developments had strict rules regarding gender. During this accelerated times the bourgeois woman’s place existed within the home and its grounds, in the defiance of these unwritten rules one could risk ‘losing one’s virtue, dirtying oneself’ [6], severely damaging the name and standing of both herself and her husband, but also the femininity in which she represented. She would only leave the house by escort of her husband, but was still restricted to where she could be taken; certain areas of this new society such as the brothels were considered unladylike which is why the works of Cassatt and Morisot are restricted to such scenes as the park and the theatre. Bourgeois males on the other hand existed as Flâneurs soaking in the social atmosphere being free to roam on their own to all areas within this new world whether they represented class and glamour or smut and sordidness, he was the true free citizen.

Cassatt’s close proximity figures examine this regarding her own situation; the close proximity to her subjects act as a metaphor towards her lack of outward mobility and confinement to being escorted around destinations. The two girls are possibly her immediate family which she required in order to visit the scene, as escorts and subject depicting the era’s gender gap, the closeness of the figures and the off centre canted angle are not elements of choice but of the limitation in which she suffers whilst attaining the shot she.

Degas Brothel monoprints, which he created between the years of 1875 and 1885 are anecdotal and caricatural, closer to journalistic images and photos in scale, medium and language. Perfectly situated within their journalistic nature is their political meaning that permeates throughout the collection; Duchâtelet’s study of Nineteenth Century Parisian society explored the idea that prostitution was endemic due to natural male demand and a regular supply of filles from a morally defective class of women. As an open prejudice to the Proletariat, these “sperm sewers” were suggested to be mentally ill, the weaker sex, subject to outbursts and emotional displays, opposed to pure and virgin middle class women. These working class women were the corner stone of urban sexuality’s structure through their economic, legal and moral inferiority which was used to preserve the respectability of the middle class women.

His prints in general arevulgar because they are not situated in the manner traditional to the reclining traditional nude, yet despite this deviation, the images are reminiscent of old master iconography through composition of setting. Rather paradoxically, these attributes are also mixed with those of Nineteenth Century pornographic prints; only pornography identifies the viewer as the lover through a gaze which is met, whilst in Degas’ prints the gaze is absent and oblique creating a double artificiality in which the female is made unavailable, in turn a rift is created in which desire is no longer present and reverts instead to disgust.

Degas’ Relaxation [Black ink on

Le Client Sérieux [Black ink on white paper, 210 × 159, 1879-80] shows similar traits and presents to us glorified lumpish women, bovine with worn provocation, cavorting and sprawled lewdly in hysterics. These attributes are emphasized by several more vulgar metaphors such as the customer’s phallic umbrella. It stands limp as hesitant and its wielder’s presence becomes peripheral, and the scene becomes a shabby representation, opposed to one of pleasure. Again it is almost as if we are placed outside the scene becoming a neutral onlooker, in opposition to Cassatt and Morisot who place us within the claustrophobic confines of their space. The ‘through the key hole’ effect is again emphasizing the disgust Degas feels towards these women despite the engagement he most likely had with them. They are grotesque to him due to class difference and inferiority opposed to that of their bodies, and thus makes himself and ourselves unavailable to them through the subtraction of spatial elements

[1] Anne Distel, ‘Catalogue for the Exhibition 1871 – 1880’, Renoir Exhibition Catalogue, Haywood Gallery, London, 30 January – 21 April 1985, Galeries Nationales Du Grand Palais, Paris, 14 May – 2 September 1985, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 9 October 1985 – 5 January 1986, (Great Britain, Arts Council of Great Britain, 1985), pp. 203

[5] Griselda Pollock, ‘Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity’, Vision and Difference, (London, Routledge classics, 1988), pp. 75

No comments:

Post a Comment