“WACK!”

‘Most of the interesting American artists of the last thirty years are as interesting as they are because of the feminist movement of the early 1970s. It changed everything’ –

Consisting of 119 artists, activists, film makers, writers, teachers and thinkers, “Wack!” was an exhibition held at the Geffen contemporary at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. Based upon the notion that feminism has caused a fundamental change in art practice, critiquing its assumptions and structures of methodology; it suggests gender to be a fundamental category for the organization of culture, patterning organizations that usually favour men.

The title recalls the bold idealism of the 60’s and 70’s and stresses that the impact of Feminist art is yet to be theorized and accepted by academic institutions and the violent and sexual connotations reinforcing feminism’s affront to patriarchy.

The exhibitions aims were to make the case that feminism in the 1970’s was the most influential “movement” of the post-war period seldom cohering to other movements such as Abstract Expressionism and minimalism. As an independent entity Feminism constitutes an ideology of shifting criteria, influenced by a myriad of factors; an open-ended system sustaining self-critique and containing wildly divergent political ideologies and practices.

The artists presented in “WACK!” characterize throughout their work that feminism coexisted with political engagement on fronts of race, class and sexual orientation, opposed to a more selfish goal to liberate women.

Strategy – curatorial procedure likened with the excavation of material traces and fragmented histories, recombined into stratigraphies to produce new meanings and insights on reality in order to specifically addressing the encounter between work and viewer.“WACK!” hopes to invoke feminist art’s romantic striving for reorganization of hierarchy and exalt the different ways feminists positioned themselves within feminism through resistance and the disruption of canon formation, supporting narrative functioning within different frames of the organization.

Whilst the show does not include male artists, the structure is told in terms of women who pioneered feminism, this could however be viewed as an equitable situation based upon socio-political gender-based mandates such as the “all-women show”, and whilst the show appears to hold no discrimination towards men it appears that it may be placing the artists exhibited into the gender-stratified groups that white, male institutions have been placing them in for centuries. Whilst it was considered as to exhibit the works of male artists, it was eventually rejected which I personally find to be at the show’s disadvantage; there are plenty of male artists speaking on behalf on gender, class and racial equality and the rejection appears to segregate them from a highly important show.

Whilst the exhibition utilises lesser known artists such as Zoe Leonard it also exhibits works of much more well known practitioners such as the Guerrilla Girls, Eva Hesse and Barbara Kruger. The exhibition exists in regards to the expansion of feminine art and whilst many artists in the show were not actively a part of the feminist movement, it is through their successes as individual women that transcended boundaries of inequality. The more overt examples such as Kruger and the Guerrilla girls specifically adorn a sense of feminism deeply rooted in both rebellion and informative gesture, and their addition to the show is in effort of their great contributions to feminism over the years and of course to their significant value throughout popular culture. This addition creates a commercial based element to the exhibition not only generating greater publicity but also breaking any pre-conceptions that feminist artists are confined to underground movements. Whilst the broad range within the show is necessary I believe that through reaching a wider audience using “big-names”, a larger amount of people may be educated about the inequalities fluent in art institutions today

Barbara Kruger Untitled (Man’s Best Friend), 1987

Silkscreen on canvas, 242 x 278cm

Kruger has been producing graphically striking, visual pieces since the 1980s in order to address the ideological structures of sexism, political authority and consumerism. Kruger juxtaposes concise and multivalent slogans in bold red and white italics over black and white photographs in order to employ visual conventions of advertising to draw the viewer’s plane of vision. The frequent use of interrogative statements such as “I”, “you”, “we” or “man” she disrupts the viewer’s passivity, becoming conscious of their individual identities.

The title reminds us of the cliché of “A dog is man’s best friend” linking domestic dogs to their human masters.

However, Kruger simply places “Man’s Best Friend” over an image of the Supreme Court Building in

Created during the Reagan years of the 1980s, the piece draws to attention how gender equality is propagated even on the surfaces of monumental public architecture. Despite the promise of equal justice, Reagan denied recognition of women’s rights and notoriously opposed the equal rights amendment. Even the composition and framing suggest an exclusive institution as her text stands in the way of the buildings main entrance and the inclusion of the female allegory named the “Contemplation of Justice”; as an abstract concept opposed to an active participant in history, submissive like man’s other best friend, the dog.

Guerrilla Girls

The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist, 1988

Offset print on paper, 43 x 56cm

Emerging during the 1980s, “activist” artists the Guerrilla Girls came to represent a useful and much needed awareness of the inequalities within the art world but encouraged a ‘niche of resistance, a militant model of representation that adopted self-awareness as action’ [2]. These veiled mystery artists unmask the discrimination on accounts of race, sex and the use of female stereotypes of virgins, mothers, whores and goddesses circulating throughout institutions such as MOMA. Using the unique concept of parasitic art the group spreads the word using the media through fliers, posters and postcards in a similar fashion to Kruger in order to exploit an exploitative means of spreading discriminative ideologies. The group continues to remind us that in the twenty-first century works by female artists are still worth less than those of their male counterparts.

Here we find the use of sarcastic humour to embody the disadvantages of being a woman artist, yet turning them on their head in order to cite ironic evidence of the advantages that men directly receive from these transactions. The amusing anecdotes whilst bringing a smile to the face highlight the lack of recognition women artists gain throughout their careers, the stereotyping of works being labelled as feminist and the pomp and bravura of upper-middle class opening nights that women need not be pained to attend.

[1] Cornelia H. Butler and Lisa Gabrielle Mark, WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution,

[2] Cornelia H. Butler and Lisa Gabrielle Mark, WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution,

Kiss, Kiss, Bang, Bang presents a similar show aiming to congratulate 45 years of feminism in the arts. The show has relatively the same manifesto as “WACK!” in its goals to voice feminism as having an enormous impact of the visual arts. The exhibition concerns who represents whom and questions the different systems of representation and continue to construct stereotypes regarding gender, race and sexuality and like its contemporary shows only female artists in order to place emphasis on the political questions posed by feminist art, in order to pay tribute to its pioneers and successors; like “WACK!” the exhibit insists that it does not belittle male artists in the process of this selection.

As I have stated, the exhibition appears to mimic the previously discussed show through its emphasis on reacting against predominant and elitist traditions of art history, fighting for civil rights for women and other minorities and to make women visible within the contemporary arts; yet unlike “WACK!”, I find it unsettling that in the same paragraph that the introduction quotes Linda Nochlin with her question “Why have there been no great women artists?” this very same source is contradicted. Whilst the catalogue addresses the inequalities of the art world it states that ‘In 2007 we are able to verify that there certainly are great women artists, but it is essential we do so at the top of our voices and do not tire of the effort’, yet Nochlin’s text states that through attesting this point we can only reinforce the negative implications that they are absent in art history. The exhibition appears to value the celebration of feminist artists opposed to the exposal of inequalities they have worked so hard to achieve.

Rasheed Araeen

‘How do I, a non-European, relate to the European society I find myself living in but do not belong? How do I react to its assumptions of white supremacy?’ [1]

1964 - Moves to

1973 - Becomes a member and active contributor to the Black Panther movement in Brixton

1975 - Joins Artists For Democracy and begins writing about art in relation to the position of Afro/Asian artists working in

1978 - Founds the magazine Black Phoenix, which only published three issues

1979-1980 - Becomes a member of the Visual Arts Advisory Panel of the Greater London Arts Association

1982 - Starts Project MRB, an art education in multicultural

1984 - Expands MRB into Black Umbrella in order to establish an Afro/Asian peoples' visual arts, resource and information centre for the training and teaching of multicultural art

1987 Publishes Third Text, a quarterly publication aiming at developing historically and theoretically informed Black and Third World perspectives on contemporary visual arts

Araeen showed in only five group exhibitions in fifteen years, and it wasn’t until age 44 that he gained his first one-person show. Mostly unrecognized throughout his career (despite winning the prestigious Liverpool John Moore’s Painting Prize), he created great significance in British art in relation to race self-representation. During the 1970s, new approaches regarding cultural identity and a growing dissatisfaction with ideological implications of modernism arose, he felt that living in a society where access to his own institutions and frames of reference were denied – it was here on that Araeen expanded his work unto race politics.

Working within the modernist era of studio based practice, he found his surroundings to be inappropriate and fewer opportunities to show his art. This transcended his practice unto art writing in which he wrote ‘Making Myself Visible’ (1984) stating that to ‘challenge[d] the established mainstream has been the desire for self-representation of those who have been formerly represented by others’ [2]. It is through this engagement that Araeen was able to actively engage in writing and shaping art history, the book is a shameful indictment of the British art establishments assertion of privilege and exclusivity, juxtaposing Araeen’s pursuit of means and strategies to enable personal, political and cultural relevance.

During the 1980’s, the decade of equal opportunity policies and the promotion of black artists, a new rhetoric was formed in white institutions to stress a visible commitment to black artists. It appears that in some shape or form, Araeen’s persistence forced issues of cultural identity and race politics into cultural debate, engendering reassessments and dissent.

However, these supposes improvements remain open to questioning as an apparent acceptance by the art world of manifestations of revolt can merely be a subtler retention of control – claiming self representation is still subject to power structures where black artists have minimal access.

Araeen’s retrospective showed at the Ikon gallery in

The majority of Araeen’s work since the 1970’s emphasizes the spectator’s position as culturally specific, implicating different positions of hierarchy. His work focuses on the unstable relationship between representation and the subject in terms of power and struggles for the right to self-represent.

I Love it, It Loves I 1978-83

Twelve colour photographs with text, both in Urdu and English

.jpg)

In this piece the Western viewer experiences extreme disorientation as the twelve colour photos are arranged chronographically from right to left, making little sense to the Western reading preferences moving from left to right. This visual narrative cannot be read due to its Urdu script and forces the viewer to move closer to read the small font English translation underneath, the visual coherence from the systematic arrangement disintegrates into a glimpse of detail and fragments as the viewers vision is concentrated, refusing to fall in place and ordering the reader’s presence in relation to the work.

Here, the Urdu speaker is in a privileged language position whilst the Westerner is denied centre stage, being forced to move back and forth in order to understand the narrative. The piece provides recognition of cultural and hierarchal difference placing the Westerner in a position to understand and sympathise with Asian artists, opposed to aiding as an act of revenge.

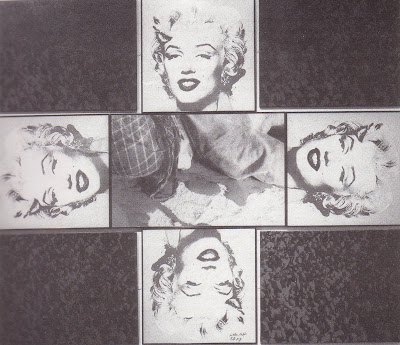

Golden Calf 1987

Mixed Media.jpg)

Golden Calf juxtaposed Warhol’s Marilyn as an icon of a globalized masculine desire contrasted with silkscreen photographs of mourning Iranian women (a stereotype of non-Western female victimization), both appear four times throughout the painting in self-conscious repetition.

In the centre lies a single dead Iranian soldier in a pool of his own blood, this aestheticisation of death is the literal scarification of a son (opposed to I Love it, It Loves I’s goat) and reserves the religious ritual of the blasphemous Jewish idol, the golden calf. Through this idolatry, the mourners become corollary to the individual image as absolute fetish, they are equally anonymous and abstract. Both images represent masculine desire, with the significance that the Iranian soldier must be dead in order to enter Western media and yearning.

Represented at death the soldier marks the site of incommensurability, a return of the repressed played out in hysterical emphasis on the irrationality and uncontrollability of this situation.

Through the numerous repetitions within the piece we find an articulated surplus of the images which self-consciously juxtapose combinations of the visual material used. Araeens places discourses of himself as the other, the ethnic, indicating the limits of such stereotypes.

[1] Rasheed Araeen, 1979

[2] Angela Kingston, Antonia Payne, Rasheed Araeen, From Modernism to Post-Modernism, Rasheed Araeen: a Retrospective: 1959-1987,

Bibliography

Araeen Rasheed, The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-war Britain, London, South Bank Centre, 1989

Angela Kingston, Antonia Payne, Rasheed Araeen, From Modernism to Post-Modernism, Rasheed Araeen: a Retrospective: 1959-1987,

Sonia Boyce

.jpg)

Boyce’s unsettling, unnamed and indefinable objects are made from her own hair, secreting an air of magical contemplation. Throughout her exhibitions they are allowed to be touched, and invite this desire, expressing personal fantasies and imaginings to create the ultimate fetish object.

They express the relationship between the public and private creating a spectacular triangle of the artist, viewer and object. Using the tension of what is familiar on one hand and uneasy and discomforting on the other, these objects of fear and desire balance on the edge of humour and terror becoming either playful wigs or human scalps as fragments of absent bodies, specifically the artist herself.

.jpg)

The hair sculptures play sardonically on the difference between the sexual fetish of Freudian theory and the fetish of colonial discourses in Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks [1]. Skin becomes the very signifier of cultural and racial difference in stereotype; it is the most visible of all fetishes and recognized by common knowledge in a range of cultural, political and historical discourses, playing a part in racial drama enacted in colonial societies. Pieces and fragments occupy the “zone of indiscernability”, they are seen and unseen, causing the sexual and racial combine in the post-colonial metropolis.

These ‘metonymic signifiers of race [are] partial indicators of “blackness”’ [2] mark a simultaneous presence and absence of black people in our society, defying reduction of racial difference into a singular, undifferentiating sign and becoming a myriad of signs remaining inconclusive without the viewer to complete the narrative. Boyce’s hair sculptures collapse the distinction between object and viewer and whilst as the artist is absent, she is party present through the remains in which she left behind. The object on the other hand can become part of the artist, the viewer (as a wig) or simply independent by itself. Her work insists on the primacy of the body and, an implicitly present trace of anonymity.

[1] Frantz Fanon, Black skin, white masks, translated by Charles Lam Markmann, New York, Grove Press, 1967

[2] Gilane Tawadros, Sonia Boyce – Speaking in Tongues, London, KALA Press, 1997

Bibliography

Simone Alexander, Zarina Bhimji, Sonia Boyce, Allan de Souza, Keith Piper, Employing the image [videorecording] making spaces for ourselves, London, Arts Council of Great Britain, 1989

Frantz Fanon, Black skin, white masks, translated by Charles Lam Markmann, New York, Grove Press, 1967

Gilane Tawadros, Sonia Boyce – Speaking in Tongues, London, KALA Press, 1997

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)